VILKAVISKIS

A small town in Southern Lithuania

Where the Jewish Community is no more

Growing Up Under Russian Rule 1815 - 1914 Part 7

BUSINESS

THE MARKET PLACE

The Jews were ‗townspeople.‘ Some of the large streets had cobblestone pavement; the other streets and the market were unpaved. On rainy days the mud was ankle-deep. . . . The immediate surroundings of the town were dotted with villages. Their inhabitants were in the main poor peasants who had to supplement their meager incomes by doing chores in town or laboring in the forests. . . . In the course of the nineteenth century conflagration destroyed homes and stores and the town was continually being rebuilt and its external aspect improved with substantial two-story brick structures. ―Before World War I, wells were covered and water was obtained by a pump. In summers, people bathed in the river, in winters in the bathhouse, according to a description of a similar community. The marketplace was the business center , as it was in most neighboring towns. Gravel and sand roads connected the villages and farms and were vital passageways to the market, on market days, wagons laden with grain and farm produce filled every inch of the marketplace. A depot for carriages stood in the marketplace, replaced in the 1940s with autobus stands. Businesses often thrived based on location. All of the community essentials for survival were centrally located, including a shpritsarmye [firehouse] with its firefighting equipment, alarm bell, and water pump and barrels.

On market days there were often displays of bric-a-brac, cheap jewelry and earthen pots. Large loaves of bread, cheese, and other farm products, such as butter, eggs, and, when in season, fruit, spinach, and wheat were also available. Behind the booths were stands to house the wagons used for hauling sand, cement, and other building materials. Both iron and structural steel were sold at the market. A farmer would come to purchase iron to build a wagon. From his sermige (in Lithuanian) [overcoat] he pulled out a stick the size of the hub. From his pants pocket he would produce a string with notches on it, the various lengths of the frame, springs, and so on. When all the measurements via sticks, string, and wires were completed, the farmer would go home happy with all the materials needed for the wagon he planned. Shetske [chopped straw] used to feed cattle was prepared with a machine and knives worked by a large pulley wheel and was a commonly sold staple in the marketplace. When the roads were dry, farmers easily transported their goods into town. In winters, roadways blocked by heaps of snow, blizzards, and rain and sleet, made traveling nearly impossible. During fall and spring, when mud corroded the axles of the wagons, many Jews earned their living as a korobeiniks (Russian) [country peddlers] by going to farms, buying agricultural produce, and then selling it for a profit in town at the marketplace. Most of the Jews earned their living in trade and skilled labor crafts. The marketplace was brimming with many other stands that contributed to the bustling atmosphere where sounds reverberated in a constant movement of life. Animal noises from cattle, chickens, geese, hogs, and the trotting of horses reflected the primarily agricultural character of the Eastern European economy. The cacophony of laughter of farmwomen, the commands of police directing the wagons, and the trading and interactions among residents within the community all bore witness to the vivacity of the village life. Trading continued until late in the afternoon, when the peasants who haggled and bantered with the Jewish traders finally returned home. At the end of the day, the wagons, now emptied of produce but filled with newly purchased merchandise, rolled home carrying items such as dishes, percale and gingham fabric for women‘s dresses, as well as boots, suits, hardware, lumber, leather, and harnesse.

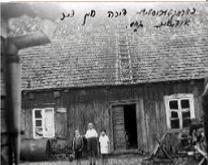

THE CUSTOMER, THE FARMER

Early on Wednesday and Friday mornings, especially in the summer, peasant farmers came to town with their wagons full of produce and livestock for sale, including hog-bristles, homespun linens, chickens, flax, and wheat. Farm women sold eggs, butter, and shtshav [sorrel, a green leafy plant]. The major customer for the Jewish stores and beer houses was the poyer [peasant farmer]. Because of the intense competition, it was difficult even for savvy business people to earn a living. Most retailers worked hard to retain loyal customers and each store offered bigger and better bargains to lure farmers into their businesses. Peasants haggled and bartered with Jewish traders and retailers, and storekeepers worried until a sale was finally concluded. Profits were desirable; consummating the sale, collecting the Russian monetary ruble or a veksl [promissory note] was the desired goal of the storeowner. The constant need for money resulted in an exchange of enticement and continued bargaining. For example, when a farmer entered a store, the storekeeper and his wife tried to convince the farmer-buyer what a great bargain they were offering and how their goods would benefit the farmer. Salesmanship skills were employed to land the sale, even though there was little profit in the sale and the merchandise was often sold at or below cost. In these situations, the storekeeper said, Es zol azoy nit trefn [it should not happen like that] after the poyer listened to the offer, gazed at the storekeeper who thought he had landed a sale, and after a long silence, the Lithuanian-speaking farmer would suddenly say, ―Taip, taip, bet ka maci?” (Lithuanian) [―Yes, true, but what‘s the use?‖] After these words poured from the farmer‘s mouth the sale was lost, and the merchant would sadly place his goods back on the shelf. When a deal was finally agreed upon, buyer and seller would end their bargaining session by clasping hands. Because literacy levels were low among the non-Jewish population, most contracts were oral.

The besmedresh and synagogue. Services were conducted three times a day. The besmedresh possessed a rich collection of books. The public bathhouse and liquor store also were close to the market. Bread, herring, salt, and spices were sold in the market, along with other merchandise, such as kerosene, and boots. Booths selling soda water and sweets lined the sides of the main street.

TRAVELING AND INNS

There were no railroads in Vilkaviskis and the surrounding towns. Instead, the nearest railroad station was in Shelmi near Vilkovishk. The most notable road went straight to the Russian-German border town, Kibarti-Eitkunen, and most travel in the region was by a karetke [horse-drawn carriage]. All of the freight was carried by drabines [wagons] also drawn by horses.99 After hours of strenuous traveling, the traveler found rest at the kretshme [inn, tavern or roadhouse], which was an important institution, serving as both a gateway for travelers and a social arena. There were several kretshmes usually near the end of a town on a highway where traffic was the greatest. In the kretshme both Jews and non-Jews could expect to find a gutn bisn [good morsel to eat] and a drink of shnaps [whiskey] or beer. The horses had to be fed and watered and there was a big barn behind the kretshme for this purpose, as well as a place where a traveler could stay with his horse and wagon and wait until a storm cleared, or in the winters, when heavy snow clogged the roads, for the road to clear up. The kretshme offered travelers lodging and shelter as well as friendly interactions with the inn owners and other residents, such as neighboring farmers who used the facility as a social club to converse and drink alcohol. Often when excess drinking occurred, customers fought among themselves, and the skilled kretshmer [innkeeper] mediated and quelled any brawls. A carriage driver packed into his cab as many passengers as possible to garner a larger net profit for each individual trip. The best roads were laid with crushed stone, but most roads offered rough rides because of bumps, mudholes, and generally poor maintenance. Oftentimes, horses were overworked and undependable, and passengers had to push the carriage over unmanageable obstructions.