Kalvarija

A small town in Southern Lithuania

Where the Jewish Community is no more

Kalvarija pictures and stories

December 16, 1999

Ten Years After the Wall

Memories of lost family are conjured when walking in footsteps of the past

By Ruth E. Gruber

On a frosty November morning, I walked around the two massive, ruined synagogues that form a unique surviving Jewish complex in Kalvarija, a small, sleepy town in southern Lithuania near the border with Poland. One of the synagogues was built in the early 18th century. Its roof had fallen in and its bottom windows were bricked up, but it was possible to see arches and other architectural detail and decoration. The other, built in about 1803, was more or less intact, but crumbling. Between the two stood a red brick building, a former rabbi's house and a cheder, or Jewish school, with a big Star of David above the door.

As I have done in hundreds of other cities, towns and villages in more than a dozen countries, I took pictures of the synagogues from every angle. With my eye focused through my camera, I didn't watch where I was walking. Suddenly, I tripped over a broken brick, half buried in the uneven yard, and went crashing to the ground. Trying to save my cameras, I ended up twisting my ankle so that I could hardly walk. The injury took weeks to heal fully, but everyone told me that my spill was beshert -- fated -- and maybe it was.

Kalvarija is the town from which my great-grandfather, Pesach Susnitsky, emigrated some 120 years ago, ending up in the small town of Brenham, Texas. In Brenham, Pesach became Philip. He was the patriarch of a huge family of children, including my grandmother, who was born in Brenham, and a pious pillar of the Jewish community.

In Brenham, he helped found a Jewish congregation. The little wooden synagogue that was built in 1894 still stands.

When he left Kalvarija in about 1880, Jews made up more than 80 percent of the town's population. By 1939, it had dropped to about 25 percent, but still about 1,000 Jews lived in the town. No Jews live there today, and I must say that given the depressing and bloody history of the town and region during World Wars I and II, and decades of later Soviet domination, I am enormously thankful that my great-grandfather had the courage to leave when he did.

Still, the buildings I was photographing were not just fascinating sites of Jewish heritage in general: they were the places where my ancestors worshiped and studied.

The streets of the town, with their small, mainly low wooden houses, and the central square dominated by a big, white church with two ornate towers, were the streets and square where my ancestors walked. I had driven there with a friend after spending the night near the Polish town of Suwalki, about 20 miles to the south. Until a few years ago, such a day trip from Poland to Kalvarija would have been difficult if not impossible.

For one thing, American citizens today do not need a visa to enter Lithuania. While Kalvarija is the first town in Lithuania across the border from Poland, the border crossing-point was opened only four years ago. I didn't have a real genealogical agenda for my visit -- I just wanted to see the town. But I had hoped to spend much of the day walking through the quiet streets, poking into corners and possibly talking to local people.

My injured ankle cramped my capabilities, though -- and here's where beshert comes in. An old woman told us where the Jewish cemetery was located, on the other side of the little Sheshupa River that winds through the town, and my friend and I decided to drive straight there.

Pesach Susnitsky died in Texas in 1939 at the age of 83. Several years ago, I visited his grave in the Jewish cemetery in Brenham. I had little hope of finding any Susnitsky graves in Kalvarija, but I was eager to visit the cemetery just to see it. We found a small, fenced-in, triangular plot of ground right in front of a huge electric grid, which contained several dozen simple tombstones, some of them toppled. Hobbling, I starting photographing the site. Just then an old man came by, wheeling a bicycle. "I know everything, everything," he smiled. All his teeth were capped in gold. "I remember everything how it was." He propped up his bike and began to talk. He described how the cemetery used to extend much, much further, stone after stone, all the way down to the river, but the Germans destroyed it, and most remaining stones were stolen.

Now on top of the area, there are ugly, poor barracks where people live -- with no indoor plumbing, they have to walk 50 yards or so to toilets. Pigs and dogs frolic around. A man passed by leading a cow. Of the remaining graves, the only mausoleum, he said, was that of a certain Menashe who was a "millionaire." I asked the old man if he remembered the Susnitsky family -- and he did. "Of course! There were a lot of Susnitskys here, a lot." Particularly, he said, before the war, there were two Susnitsky brothers in town, Alter and Yankel, who must have been nephews or great-nephews of Pesach. "Alter was a big, tall man," he said. "Yankel was small, curved over and had a hunch back." He demonstrated, scooping out his own body.

The brothers lived together in a big house on a hill, he said -- and then he led us there to see it. Indeed, it was one of the most imposing wooden houses in the village. Undergoing some renovation, it even sported a satellite dish. Both brothers were killed when the Germans deported the Jews to nearby Mariampole during World War II, he told us. The old man said all the houses on this street were occupied by Jews, and that Jews lived all over the town. "So many, so many!" He gestured forlornly. He was clearly nostalgic for past times -- and the disappearance of the Jewish community represented for him a change for the worse. Nonetheless, in describing the Jews in town, he used the Polish term Zydek or "little Jew" -- a term Jews regard as pejorative.

The Jews in Kalvarija were "good people," and "wealthy," the man said, they took care of each other and everyone got on with everyone.

"They were called Yankele, Alterke, Menashe, Meyshke," he recalled. "They would say, 'Oy vey, oy vey.'"

JTA senior European correspondent Ruth E. Gruber is the author of "Upon the Doorposts of thy House: Jewish Life in East-Central Europe, Yesterday and Today," and "Jewish Heritage Travel: A Guide to East-Central Europe." She has documented Jewish heritage sites in more than a dozen European countries over the past decade.

Maushe Segal, the Last Jew of Lithuanian Kalvarija

Ten Years After the Wall

Memories of lost family are conjured when walking in footsteps of the past

Click on the picture to read his story

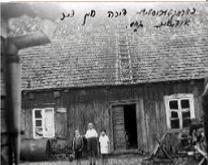

These pictures are from the family album of Janet Ghiandoni from Cleveland, Ohio.

In appreciation to Janet

The picture was labled "Belle's Aunt". It was taken in Marijanpole. Since I don't yet know of any relatives that were from Marijanpole and since I don't know who the couple is and until five years ago my family believed that that was where their ancestors were from I am not sure what to think.

My great-great-grandfather Meir Kavadlo. He was born in 1831 and as of yet I am not sure where. He was a blacksmith in Kalvarija until around 1920 when I believe the picture was taken. The woman seated next to Meir I believe is his wife BashaSimkovsky. The mother of another synagogue neighbor said her family owned a hardware store located where the hardware store is today. Together Basha and Meir had at least seven children. The man in the bowler hat standing behind his father is Tachen Kavadlo who owned a tavern in Kalvarija and lived on Garbarskaya Street in 1908. The three of them, as far as I know, were the only ones to remain in Kalvarija. A daughter of Meir's married and moved to Seta.The rest of the family moved to the United States between 1871 and 1900.

This picture is of Jacob Kavadlo(Myers) (Tachen's Son) and his uncle Itzko Kavadlo(Myers). The family changed their name when they came to America. This picture was takenbefore 1900 when they were in the Czar's Army. I wish I knew the story of how they escaped because it is my understanding that enlistment for Jews was a life sentence.

These two pictures were kindly provided by Micha Reisel

Here is a picture of my great -grandmother Chaye Sora bat Mordechai Zvi Smolizanski, Chaye was born 5 May 1843 in Kalvarija (died in NY in 1916)

A picture of her brother Jacob Wolf Zeev Smolizanski born in Kalvarija in1853 died 1932 in Rishon le Zion, where he was the first director of the Carmel Mizrachi Wineries in Rishon, since 1902 He moved to Rishon in the 1890s from Riga where he lived and was director of the Grain Exchange In Rishon he also was a member of the Moatza and a street is named after him and his brother Moshe Nisan (the street in Rishon is called Achim Smilizanski, and I have asked the iriyah to change it to Smolizanski but never heard from them again...)

This picture was kindly provided by Connie Buchanan

For more pictures of Connie's family and information click here

KAPCIAMIESTIS, Lithuania