What life was like under Russian Rule

VILKAVISKIS

A small town in Southern Lithuania

Where the Jewish Community is no more

HISTORY FROM IMMIGRANT RECOLLECTIONS RELIVING THE PAST

What was life like for Jewish families who lived in Vilkaviskis during the decades between 1894 and 1911?

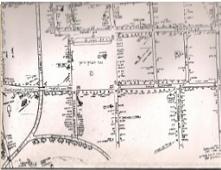

FAMILY LIFE CONSTRUCTING A HOUSE

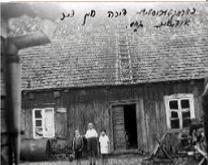

Building an ordinary one-story house took three or more years to complete. 32 First the builder and his helpers went to the forest where they cut down the necessary trees. After measuring and re-measuring, they carefully sawed, chopped, hewed, and planked the trees until they formed the needed logs, boards and siding. This took about three to four months. Then they brought the lumber to town and laid it out on the market place field and the joists and planks were fitted taking another three to four months. Next came the foundation, and sometimes it was necessary to dig a cellar. Another three or four months were needed for framing the building. The siding, brick laying, and plastering consumed yet another three or four months. The roof, floors and final touches took additional time.

THE HOME AND FURNISHINGS

At the entrance to an average home in Vilkaviskis stood a kayle [barrel] filled with drinking water with a copper dipper on top, as well as an almer [cabinet that stores food] nearby. The almer contained ayngemakhtsn [preserves] with a warning: ―M‟zol dos nit darfn.” [―You should not get into it.] Next, situated in the kitchen was a koymen [chimney] and a plite [brick or earthen stove]. In winters and nights, below the kamen [brick fireplace used as an oven] sat a katukh [chicken coop] with eggs. A container for pots and pans was accessible. Located nearby were a shlof bank [folding bed] usually painted red. When the lid lifted, the bench interior became a bed with the straw tick mattress and pillow in the drawer below. There was also a table, a kerosene lamp, and a politse [shelf] for pots and pans. Next to the kitchen came the living room. Its walls were decorated with pictures and photographs of the mishpokhe [family]. The furniture consisted of a vant zeyger [wall clock] with weights hanging down and a chain to wind it up, a kushetke [sofa] which served both as a bed and hope chest, tables, chairs, wooden clothes closet and a kakhloyvn [tile oven]. The bedrooms were mostly side rooms: one shared by the parents with the infants and two others, one for girls and one for boys. The furniture was simple, plain and wooden and passed on from generation to generation. Some homes had a commode. Each home had a bookcase filled with books, mostly of a religious nature. The walls were either calcimined or covered with paper. A sheygen [woven runner] covered the floor. On Saturdays some families spread fine yellow sand on their floor lekoved shabes [to honor the Sabbath]. Homes were lit by kerosene lamps. The blitslomp [bright lamp] hung from the ceiling was lowered or raised by a pulley attached to a heavy weight on the bottom. The glass-bowl kerosene lamps and glass chimney lamps produced smoke and their wicks had to be trimmed continually. The smoke and soot needed to be wiped from inside the chimney. Around 1905 a new resource, carbon gas, was used to illuminate the streets. The first direct electric light was powered by a generator in a steam-driven flourmill. The small and dim bulb flickered constantly and a kerosene lamp was kept on hand if needed. After the German occupation during World War I ended, the marketplace was lit by electricity. The streets were paved with cobblestones and the main highways leading out of town were paved with crushed stone.

WEEKDAY MEALS

In the mornings, mothers prepared lunches for their children to take to school. Usually the meal consisted of bread smeared with shmalts [chicken or goose fat], and kompot [fruit dessert] as well as juice. Herring: Litvaks [Lithuanian Jews] prized a slice of herring. Smoked, pickled, or chopped herring were popular home meals. Smoked fish alone created a meal. Fish was less expensive than beef and was a popular dish because the area was blessed with nearby rivers and the Baltic Sea. When the ice broke up in the spring some men reduced their cost of living by catching fish in a big barrel. If the price of herring was too expensive for the family, then a kopeke worth of brine from the herring barrel with a potato had to suffice. Potatoes and herring were considered, in Hebrew, maykhl meylekh [food fit for a king]. Potatoes and Vegetables: The humble potato was a favorite staple on the tables. It was filling, plentiful and, most importantly, cheap. The folk song ―Bulbes‖ [―Potatoes‖] immortalized the potato: ―Zuntik bulbes, montik bulbes, dinstik bulbes, mitvokh bulbes, donershtik, un fraytik bulbes, un shabes, bulbe kugl.” [―Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday potatoes, and Saturday, potato pudding.] At Chanukah, latkes [potato pancakes] were served. Oftentimes, potatoes and pickles were served together as a meal. If the family had a cellar, they put away food for the winter, usually a barrel or two of sauerkraut, a keg of pickles and a few bags of potatoes, beets and carrots. Soup and Beans: When resources are low a winter recipe could be created groypn mit gornit [together with nearly nothing], using only a few ingredients such as a pot full of water, a handful of barley, an onion or two, and pepper or just with hot water and fat. When boiled, it was served with plenty of pieces of bread and a spoonful of shmalts. Stale bread was made into bread soup. Gekokhte arbes [boiled chick peas] were another popular meal. Pickles: The lowly pickle had a place of honor in the diet. Nearly every household prepared a barrel of pickles, and women took great pride concocting unique zoyer [sour] pickle preparation methods. Tea: A favorite brew in the homes was tea. It might be used as a medicine, as a warming agent in winters, and for cooling in summers. It was handy for entertaining visitors. Tea washed down a heavy meal. From Friday until Saturday afternoon tea time, the tea kettle was kept hot in the neighborhood bakery. Tea served as a filler, especially when hardship struck. When nothing was available to drive away hunger, bread and a reliable glass of tea might fill an empty stomach. The government, under Russian control, derived a generous income from duties on tea. However, thanks to smuggling from across the German border, not all of the tea came burdened with taxes. A few families made their living by bootlegging tea. A paternal aunt took pride in telling the story of how in her youth she carried tea in her bosom across the border. An account of a black market operation described how Fedorov, a local nonJewish zhandarm [policeman], was aware of smuggling but seldom made arrests. Instead, Fedorov warned people when officials contemplated a raid. Officer Fedorov and the Jews lived by a code of protection. One of Fedorov‘s female subjects wore a fatsheyle [huge shawl] under which she carried her stock of tea. When Fedorov sensed danger, he warned her, ―Ram oys dem khomets, me geyt zukhn dem afikoymen. [―Hide the contraband, there‘s going to be a search, literally, ―clean out what‘s not fit for Passover; they‘re going to look for the hidden Passover matzo.]

Goat’s Milk:

Among the most popular animals were tsign [goats]. They were inexpensive to own, since they ate whatever the family could afford, such as potato peelings, or they foraged for themselves. During the summers children enjoyed taking the goats grazing. The goats earned the title ―the poor man's cow, as they nourished the family with rich milk within the family budget. Goats‘ connection with people inspired folk songs, with metaphorical lyrics such as, ―Under the cradle, there stands a snow-white goat

MANAGING THE HOUSEHOLD

Even on ordinary days, managing a household in old Vilkaviskis was a chore. A woman‘s job was never done. Besides her household duties, she cared for a large family. A grandmother, Dvore Trivasch, bore and raised five girls and five boys. Most families‘ incomes were slim, and these women who managed large households found ways to economize on food and clothing by reusing goods so that nothing was wasted. The Yiddish-speaking women mingled among their non-Jewish neighbors as they shopped in the market, and thereby, learned to speak bits of Lithuanian and Russian. Middle-class households with young children employed servants, often several at once. The higher the class, the more servants the family had. Most Jewish families had at least one ―maid of-all-work, a non-Jewish peasant girl from a nearby village who lived in the house, did the heavy cleaning, and tended the fires. Typically, she lit the fire on the Sabbath so the Jews could abide by the scripture and avoid work on this Holy Day.

HEATING THE HOUSE

Harsh winters brought the challenge of searching for wood, turf, and old grass to kindle fires and provide warmth. Fuels were burned in brick or tile ovens for heat. Some people experienced headaches from the carbon monoxide fumes of burning turf. Chimneys required cleaning. Accumulated soot in chimneys often caused fires, and many homes burned down. The koymen kerer [chimney cleaner] walked through town with ladders, brooms, brushes, and a long rope to which a weight was tied for pushing out the soot. The chimney cleaner‘s face was usually black from charcoal, and descriptions of his appearance were often associated with an aura of mystery.

CLOTHING

Outgrown or worn-out clothes were turned inside out and made into new garments. Young, single girls sewed for customers in a shop and then they put their earnings into a family fund for their nad‟n [dowry for a groom] and for a trousseau which they collected in a big chest. When women left the house, they wore a huge fatsheyle [huge shawl]. Underneath the fabric, they carried a basket to fill with goods at the market. If someone needed shoes, the shuster [shoemaker] came to the house to take mosn [measurements], which were usually done with a strip of paper by tearing notches to indicate the shoe size. The upper sections of worn out boots were cut off and attached to a new pair of boots. The shtivl [boots], kamashn [gaiters], and knepl shtivl [boots with buttons] took longer to make but also lasted much longer than other types of shoes. Pious Jewish women after marriage wore artistically fashioned wigs. There were no signs of graying hair. In winters, people bundled up with great gray coats made from homespun wool and wore felt boots on their feet.

LAUNDERING

Washing clothes, a time-consuming and difficult task, was done only periodically. Preparation for washing clothes began by catching rainwater into large barrels placed beneath the edge of the shingled roof. Loyg [lye, a mixture of rainwater and wood ashes] created alkaline water for washing. During washdays the home took on a new look. The koymen [fireplace] was completely cleaned out, the chicken coop beneath moved, and a tripod was placed inside the fireplace. Planks of wood were laid near the open brick oven, and large wooden washtubs with plenty of long bars of soap were positioned on the planks. A large copper kesl [kettle] was placed in the fireplace over a tripod. Washerwomen came to the family home. All night professional washerwomen scrubbed and washed. From time to time, they fortified themselves with liberal portions of rozheve [dark bread], herring, and tea. The washing process was simple-they placed the laundry in a copper kettle, where the water was kept boiling, and in the morning the washerwomen took the clothes to the river or the Creek where they rinsed and beat the washed laundry with a prinik (Russian) [wooden grooved trowel]. After completing the rinsing, the washerwomen brought clothes home and hung them to dry, usually in the attic. Other laundry, when partly dry, was carted to the mangler, a person who had a contraption for drying and ironing water-laden cloth that consisted of a large wooden box on rollers and filled with rocks to weigh it down. To keep the linens smooth, they were wrapped around the wooden roller and placed under the mangle, which rolled back and forth by means of a pulley and a large wheel that squeezed out the water. When the clean laundry reached home, mothers mended the clothes and put them away ready for a weekly change.

SAVING MONEY

Women hid coins about the house or kept money tied in their garments in a knipl [little knot]. The secret currency, whether a few paltry Russian gilden or thousands of rubles, was saved by thrifty women for an emergency or for when a nad‟n [dowry] for a marriage was needed. The place where the money was hidden was known only to the woman, but she sometimes forgot the hiding place or the money was lost in a fire.

EARNING A LIVING

Some of the common occupations in Villkaviskis.

Local merchants: of herring, sausage and delicatessen, tobacco, confection, ice cream and soda water, hardware, books, woolen goods, junk, wine, and more Country peddler. Craftsmen: blacksmith and tinsmith, candlemaker, bookbinder, capmaker, wig maker, cloth dyer tailor, seamstress, shoemaker, shoe repairer, printer, photographer, watch repair, jeweler, house builder, carpenter, plasterer. Laborer: pack carrier, chimney cleaner, domestic, washerwoman.

Community service: burial society volunteer, teacher, barber, volunteer firefighter, mailman, banker/ moneylender, carriage driver, watchman, public bath for women.

Food production: grocer, butcher, ritual slaughter, baker.

Professionals: rabbi, synagogue caretaker, lawyer, druggist, medical and folks doctor.

Factory production: sugar, rope from flax and hemp, pop, flour, lumber saw mill.

Miscellaneous: infantry and cavalry soldier, musician, restaurant proprietor, roadhouse owner, beggar, and hotel operator.

The old Tsarist law had prohibited Jews from owning farmland so there were only a few Jewish farmers. Nevertheless, some city Jews rented land where they could plant vegetables.

SOCIAL, HEALTH AND WELFARE

CHOOSING A MARRIAGE PARTNER

When a girl reached marriageable age, her parents began to worry about a shidekh [marriageable match] for her. They feared their daughter would be farzesn [passed over]. The song, ―Yome,‖ [a girl‘s name] expressed the daughter‘s concern. People with means preferred a son-in-law who was educated. To pick a student as his daughter's husband a girl‘s father might travel to a yeshive [Jewish institution for where young men studied the Torah and Talmud], speak to the head of the yeshive and observe the interactions and behavior of the male students. Sheyne eydems [scholarly sons-in-law, literally, beautiful sons-in-law] were considered desirable. Although the yeshive bokherim [male Talmud students] were mostly poor, the lack of finances did not matter. The future father-in-law would provide the young man with room and board and other expenses. During the engagement year, the couple might see each other only a few times. Marriage through a shatkhn [matchmaker] was another way for a girl to find her bashert [destined] match. The job of a matchmaker was difficult. Not until the wedding was complete were the shatkhones [marriage brokerage fees] certain. In the eagerness to complete the shidekh, the wealth of the prospective bride or groom was exaggerated. Often the father promised a cash gift to the groom that he was unable to fulfill. If the groom wanted to make sure he would not be cheated, he demanded his nadn before the wedding ceremony. Therefore, it often took much bargaining to make the groom go through with the wedding ceremony. It was considered below a woman‘s dignity to marry a working man. A Lithuanian saying admonished, ―Souhas, kriaucius ne zmogusz.‖ [―A shoemaker and a tailor are not suitable.] The expression, ―In mayn familye iz keyn bal milokhe nit faran” [―In my family there were no working men‖], also conveyed the sentiment that suitable marriage partners were from the highly educated class. Although desired, some of the sheyne eydems were not as successful providers as some of the so-called lower-class working men. Many of the educated and those who adopted a lifestyle of continual full-time education had to depend on their wives to run their shop in the market and support them, while they sat in the besmedresh [house of prayer and study] and studied the Talmud. However, regarding the working man, the Hebrew saying declared ―bizies apey.” [―By his sweat he earns a living.] A man‘s wealth was judged by the size of his protruding stomach. A buxom hefty young girl took a man‘s fancy.

CELEBRATING A MARRIAGE

Not only were the bride and groom and their families kept busy preparing for the anticipated khasene [wedding], but also the entire town seemed involved with the preparations. The shames [synagogue attendant and rabbi‘s assistant] was busy distributing the bilet [ticket, wedding invitation]. Friends and families were seeking suitable droshegeshanken [wedding gifts], and the bandleader and his kapelye [musicians] were practicing their music. The family was arranging the bridal and wedding quarters. At last, the day of the khasene arrived. A wedding took a week to celebrate. The wedding party marched through the streets to the khupe [canopy] under which the ceremony was performed. Usually they walked from the bride‘s house to shul and stood before the crowd of orkhim [guests]. The musicians played the wedding march and relatives carried lit candles. The rabbi, khazn [cantor], and shames ceremoniously awaited the bride and groom at the khupe. At the end of the ceremony, the groom [khosn] broke a ceremonial wineglass wrapped in a cloth by stomping on it, and everyone shouted, ―Mazltov, mazltov” [congratulations]. The musicians played freylekhn [cheerful melodies]. The guests were invited to the wedding house to eat goyderne zup [bridal soup]. The traditional batkhn [wedding entertainer] recited drosho geshank [rhymes for the wedding couple]. The kales tsad un khosns tsad [friends of the bride‘s side and groom‘s side] danced, celebrating the joyous event. Three days after the wedding, newlyweds were invited to visit the homes of friends and relatives, a custom known as rumpl. If it was winter, the kale [bride] usually wore a new ratond [fur coat]. The groom looked bright in his wedding outfit with a gold chain and zeyger [watch], a gift from his bride. The groom‘s outfit was a tight fitting coat cut away in the front with a split back like a full dress frock.

RECORDING BIRTHS

Metrikes [birth certificates] caused worries for some people. Parents, burdened with responsibilities, sometimes neglected to register a newborn, thus creating troubles for their sons or daughters in later years. For instance, a young man who looked physically big enough to be called into the army, but could not prove his age, was taken before a military commission that opshatsn [appraised his age]. The army, hungry for soldiers, would conscript such a young man years before his legal age. A birth certificate also was needed for entering high school and when applying for a passport. Many children marked their birthdays based on holidays or specific months of the Jewish calendar. For example, ―I was born on the drite likhtl [third light] of Chanukah. My birthday is three days on elel [the last month on the Hebrew calendar] or during peysekh [Passover].‖ When Jews were uncertain about the year they were born and when they did not know their exact age, they often guessed. This proved useful for those who wished to appear younger by removing a few years from their age. A father knew he was born in August, but he was not sure if it was 1889 or 1899. His age and those of his siblings were estimated relative to events and the span between siblings‘ births.

EDUCATING THE CHILDREN

Boys and Education: Folks took great interest in their children‘s education. When a son reached age three, his father wrapped him in a tales [prayer shawl], covering his face to create an element of mystery. Thus, the father carried his son into the esteemed kheyder [religious elementary school for Jewish boys]. Here the teacher ceremoniously started him immediately on his alefbeyz . . . [Hebrew letters]. The teacher said, ―See yingl [little boy], this is alef [letter A], this is a beyz [letter B], and so on. The teacher enticed the student by promising, ―If you say your alef, beyz [letters] correctly, an angel will throw you sweets. Lo and behold, sweets suddenly landed on the alef, beyz page.

When the sweets lost their enchantment for the little boy, the angel dropped a shiny kopeyke [Russian copper coin] as the boy studied his komets-alef, „oh‟ komets-beyz „boh‟ komets-daled „doh‟ [rhyme to memorize the letters and vowels]. Sometimes the letters were covered with sweet tasting honey. (The folk song ―Oyfn Pripetshik” immortalized this ritual.) Children studied in the kheyder to learn to read and write the Hebrew alphabet. Then they studied from nine in the morning until nine at night, studying the Bible and Talmud. At age 10, they learned to write Yiddish.

Girls and Education: Girls were not given a strenuous traditional Hebrew education. If a girl went to a girls‘ kheyder for a semester or two and knew her prayers and how to write a few lines, that was considered sufficient. However, in later years, with the formation of the Jewish gimnazyes [secondary schools], girls also received a thorough education.55 The teaching was in Yiddish, except the Talmud, which was taught in Hebrew. In time, Jewish women were permitted a secular education long before other towns in Lithuania. Saul Issroff‘s grandmother arrived in England fluent in English, German, and French, apart from Russian and Yiddish, to the extent that she taught World War I officers German and Russian.

Education and Finance:

Even when times were hard, tuition money was found and boys studied with the best melamed [children‘s teacher]. Tuition was the number one item in the family budget. Families took turns, for twenty-four hours at a time, providing meals for poor students who attended kheyder or yeshive [a secondary school for boys where the Bible, Hebrew, Jewish rituals, law, and Talmud, were taught]. At the end of the nineteenth century, Russian, German, and literature also were taught in some schools. It was considered a mitsve [good deed] to feed a student, even if it meant providing the student with more nutritious meals than the family could afford for itself. If families lived too far away from the town school, they hired a teacher to live with the family during the school session. Jews in Vilkaviskis had a democratic approach for educating all children‘s Toyre lishmo (in Hebrew) [Torah study]. The yakhsonim [privileged rich] and the humble poor were treated alike. Torah instruction and secular education were sponsored by volunteers. Prominent men, mostly sons-in-law of the rich, accepted the honor of collecting charity to pay the tuition for poor children. They collected chicken feathers from the shoykhet [ritual slaughterer] to raise school funds for underprivileged children by marketing the feathers to be used for bedding. Children received a free education at the Talmud Toyre [Torah study school] sponsored volunteers. The qualifications for teachers of the kheyder were standardized. A melamed who taught in the kheyder was required to obtain a license to teach. Money was scarce and often it was difficult for teachers to raise the rubles for the required permit. Parents who wanted to send their children to kheyder also had difficulty raising the funds for shar lemud [tuition fees].

Academic Schedule:

School was divided into two semesters. The spring-and-summer semester began after the peysekh celebration, and the fall-and-winter semester began after sukes [the Sukkoth celebration]. The school hours were long, lasting from nine in the morning until two in the afternoon with a lunch break, then continuing until the evening. It was dark in winters when the children finished kheyder and they carried likhternes [lanterns] to guide them home.

School Buildings:

In early days, only one- or two-room kheyders existed and were often used for a dual purpose-both for instruction and for the teacher‘s dwelling. In addition to the elementary kheyder in various parts of town, the beys haseyfer [school building], with its scholarly and capable teachers, afforded cultural inspiration to the boys. In later years, Mariampole organized a large modern beys haseyfer with airy classrooms on the main street and classes were taught in Hebrew. On occasion, fights between Jewish students from their respective schools were carried on using sticks and stones.

Discipline:

Disobedient children at school were punished physically with the application of a kantl [―little edge, straight edge ruler] on the body. When a child was struck it was both painful and shaming. Shmaysn [whipping] the child was also a common practice.

Discrimination

A few Jewish boys had the legal privilege of attending a Lithuanian gimnazye, equivalent to a junior college or college preparatory school, but only when the enrollment did not surpass the quota of one Jew to ten non-Jewish students. Jewish parents were required to pay higher tuition, which paid for their son as well as a non-Jewish student. However, there were no quotas for girls in the private high schools, girls‘ gimnazyes. Jewish students who were not allowed to study at the Russian government gimnazyes, but were eager for an education, studied privately. They studied both day and much of the night and most students succeeded in taking the examinations for all eight required courses at once. On the eve of World War I, many Jewish boys and girls were admitted to the Russian secondary schools in addition to the traditional kheyder.

Apprenticeship:

Some boys went to the yeshive after they completed kheyder, but parents of most boys between 12 and 15 arranged an apprenticeship for their sons, preferably for what they considered refined trades, such as watch repairing, printing, or photography. The boys would serve without compensation for at least a year. Sometimes their parents even paid for the 18 months training.

CARING FOR THE SICK

Sometimes the sick traveled by train or a horse-drawn carriage to Königsberg, a German town in East Prussia about 40 kilometers away, known for its outstanding physicians. The custom of seeking a Jewish physician in Germany resulted from the fact that beginning in 1871, thousands of German Jews had graduated from the country‘s medical schools, then under the German Chancellor Bismarck. (By 1900, sixteen percent of all physicians in Germany were Jewish although Jews comprised only one percent of the population. Some German Jewish doctors attained fame for their research during this period.) There was only one medical doctor and a feldsher [folk doctor] to care for the Jews who were sick. There were no nurses, and if there had been, few residents could have afforded to pay for their services. Some boys and girls in their teens, working in pairs, organized themselves in linyes hatsedek [lines of charity] and performed night-nursing duties. They went to the homes of the sick and watched over them, relieving worn-out family members and helping with household chores. The folk doctor utilized spells, amulets, herbs, and other supposed remedies to ward off sickness, as well as cupping, the application of a suction cup to flesh to remove body toxins. For severe swelling, heated bankes [cupping glasses] were applied to the body of an ailing person to draw blood to the body surface. When a finger was cut, a spider web was applied to stop bleeding. Smoke emanating from a burning piece of gauze was used to disinfect a wound. When one felt struck by an eynore [evil eye], it was recommended to see someone who possessed the power to talk the evil away. When a person was dangerously ill, family and friends gathered around the patient‘s bed and performed opshrayen a teytn [screaming and yelling] at the patient-the louder the better. For severe sneezing, the feldsher pulled the left ear and spat three times. For sand in the eye, the lid was pulled down to stimulate tearing. To ward off an illness, the Hebrew word adoshem [word for G-d] was written around the neck of a sick person. It also was advisable to visit a gutn yid [a good Jew] for a magical cure from a suffering illness. Two generations later, when I had a wart on my finger, my - father told me to put urine on the wart to make it disappear people prescribed bobes refues [grandmother‘s remedies], such as old wives‘ tales. One such remedy to prevent colds was placing a piece of garlic in a bag and hanging it around the neck. Worm kraut was a candy medicine given to youngsters at the beginning of each month as protection against intestinal worms and rock candy was given for coughs or colds. To drive away an evil eye from a child who suddenly became sick, it was advised to talk against the evil eye. When looking at a beautiful infant, it was advisable to spit and say ―What an ugly baby. The culture interpreted and analyzed beyze khaloymes [bad dreams]. When a person had a disturbing dream, he gathered three friends and repeated these Hebrew words: ―Kholem toyve hazise.‖ [―May your dreams be good.‖] His listeners answered, ―Kholem toyve hazise.” [“Your dreams are good.] This was repeated three times to relieve the mind. People bought medicine at a chemical store with its highly polished floors and rows of shining porcelain medicine jars. The medicine was packed in a box or a bottle with attached slips that stated the contents of the prescription with the doctor‘s and patient‘s names. There was a shelter for wanderers and visiting scholars.

DYING

Life was highly valued among the Jews. It was essential to live life to the fullest, as well as humanely and ethically to form a binding relationship with G-d. According to Jewish law it is forbidden even to move the arm of a dying man, as it might shorten precious moments of his life. The scriptures tell us, ―He who takes his own life, has no part in the world to come.‖ When a well-respected Jewish man community committed suicide, the town was shocked and saddened. He was a Jewish man blessed with a wife and many attractive sons and daughters who attended the gimnazyes, and he had a well-paying job as a tailor sewing uniforms for Russian officers. ―A malady hit this family. As the children reached adulthood, they became sick and died from tuberculosis or other diseases. The father was also infected with this disease. The family kept a cow because people believed that fresh cow‘s milk is a good remedy. The father, an expert tailor, sewed uniforms for Russian officers, and there was no shortage of money in this family, but the continual tragedies weighed heavy on them. One morning when the wife returned from milking their cow, she found her husband bleeding profusely from a self-inflicted cut, which he made with a sharp razor. He died shortly afterward.

His funeral was attended not only by Jews but many Russian officials, including high-ranking officers, who cried at the untimely death of their master craftsman. Straight after the death, a yahrzeit [commemoration of death] candle was lit in the mourner's house for the ascent of the soul of the departed. If possible the funeral was soon as possible. Until the funeral, the mourner was exempted from prayers and blessings, so he can honor the dead and take care of the funeral arrangements. At the funeral, the mourner tore an outer garment, and continued wearing it throughout the shivah [Judaism's week-long period of grief and mourning for the seven first-degree relatives: father, mother, son, daughter, brother, sister, or spouse]. The men‘s and women‘s volunteer members of Chevrah Kadisha [burial society], arranged for funerals. They prepared the bodies for burial, chanted the prayers for the dead, and collected money in tin cups at the time of the funeral. The ring of the cups and the chant ―charity will save one from death accompanied the funeral procession. The poor and pious were buried promptly without remuneration by the family. Once the family returned from the funeral, the mourners were not allowed to do many things for the seven days. The shivah candle flickered during the seven days following the funeral was a period of mourning after the death. There were many rules concerning the shivah, which created a great interruption to one's normal routine to honor the dead and to help the mourner deal with his or her loss. The week of sitting shivah, the family was confined to their home and friends came for condolences.

RECREATION

The break in the daily drab existence were the weekly shabes, and holidays and the little celebrations such a